Trees, Heat and Human Health

In Providence, disparities in tree cover across neighborhoods have serious implications for health and environmental equity, with some areas left more vulnerable to extreme heat and its effects.

Walking down Benefit Street or elsewhere on College Hill, one experiences shaded branches during spring and summer and the spindly fingers of trees in winter. However, as one ventures into neighborhoods across Providence, access to trees and green spaces differs – and holds serious repercussions for the health and well-being of people who live, work or play there. “Every tree,” says Tabatha Hirsch ’25, “contributes uniquely to its ecosystem: trees have the capacity to benefit each other, to promote biodiversity, to suck carbon emissions out of the atmosphere, to bear nutritive nuts, seeds and fruit.” Hirsch’s thesis in collaboration with the Providence Neighborhood Planting Program focuses on “trees’ ability to cool down spaces for communities, which they achieve through evapotranspiration (releasing water vapor into the atmosphere) and in providing shade” to neighborhoods and locations like schools and sidewalks. Across campus, faculty and students at Brown in multiple disciplines seek to better understand and address the connections between trees, heat and health in Providence in collaboration with community-based organizations.

For almost forty years, the Providence Neighborhood Planting Program (PNPP) has been working to cultivate “a really healthy and resilient urban forest [to benefit] all of the people and beings that rely on and live in relationship with those trees,” says Jordan Schmolka, PNPP’s Director of Operations and Urban Forest Collaboration. The work of PNPP includes providing and planting free street trees by working with residents, coordinating volunteer-led planting events and ensuring proper tree placement and care to foster greener, healthier neighborhoods. Several collaborative projects, including the PVD Tree Plan, have advanced efforts to collect data and community input and use it for education, advocacy and tangible change.

Last summer, Kevin Carter ’25 completed an Institute at Brown for Environment and Society (IBES) internship with the Nature Conservancy of Rhode Island. An environmental studies concentrator who is also pursuing the Data Fluency Certificate, his work connected him to PNPP, where he organized and cleaned tree data sets, in addition to his broader work of compiling potential content for a state climate action policy plan. A student worker with the Swearer Center, Kevin brought PNPP’s work to the attention of Dan Turner who matched them to others on campus with related interests through the Community-Engaged Data and Evaluation Collaborative (CEDEC). CEDEC is an initiative of the Swearer Center bringing together partners from across Brown University to support community partners' data and evaluation priorities.

Speaking about his enthusiasm for his work with PNPP and environmental justice more broadly, Carter ’25 says, “What initially enticed me to contribute to a project for PNPP was the PVD Tree Plan because of the commitment that it made to environmental justice via equitable tree planting. I found that the overarching principles and objectives in the plan aligned with my values and interests in environmental justice and I wanted to support it in a way that would allow me to exercise my data fluency skills.” Carter ’25 was able to contribute his technical skills to the organization to support data-based projects in the pursuit of equity. The datasets he cleaned were intended to be used in mapping through GIS software “to produce geo-visualizations of the tree plantings over time so that observations could be made about how the spatiality and density of tree planting efforts have changed in relation to equity concerns.” His volunteering efforts, he says, “exposed me to the community and gave me an opportunity to serve while learning from them and being able to bring that experience and perspective back into my work made it feel much more meaningful.” Now, he hopes that his work and the PNPP project can extend into “a fruitful and promising relationship between Brown and PNPP and the city of Providence.”

“ Spatial analysis is not just about understanding what is happening. It’s about understanding where it’s happening and how that location shapes the outcome. For example, tree canopy coverage, heat vulnerability and socio-economic disparities are deeply intertwined." ”

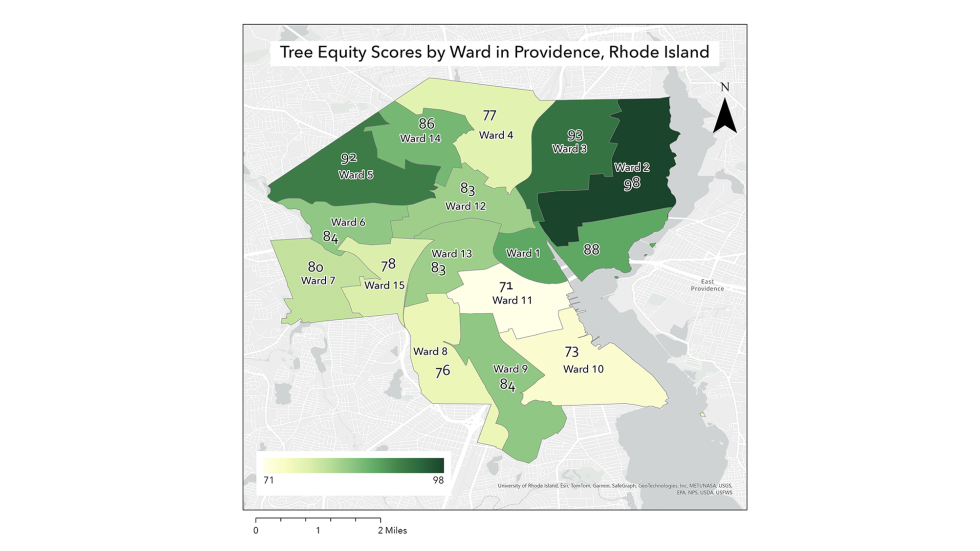

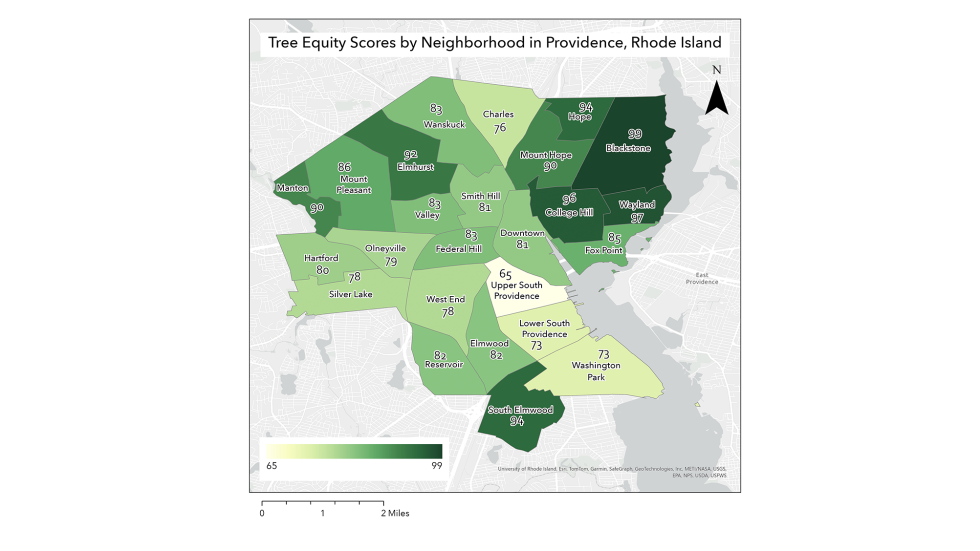

Through a connection made through CEDEC, another step in that journey was taken by Noreen Chen ’27, who partnered with PNPP in a GIS-focused course taught by faculty member Seda Şalap-Ayça of the Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences. By listening to a data priority identified by PNPP, Noreen related Tree Equity Score maps (which are done by Census block groups) to Providence neighborhoods and city council wards, geographies that align more with the way local residents may see their communities. Maps can be powerful, accessible means of communication and learning. “You look at tree canopy cover, median household income, communities of color, asthma rates, heat island effects and historical redlining, as they're all distributed spatially across the city and you see some really striking recurring patterns,” says Schmolka. Visualizing the relationship between these current inequities can shed light on their roots in environmental racism and long-term disinvestment and can inspire action for change. But Schmolka emphasizes that maps alone shouldn’t drive planning decisions—they can’t capture the full picture of people’s experience of their neighborhoods. “Community-driven decision making, collective planning,” is still critical, Schmolka says; maps may suggest a good place to plant that’s actually a soccer field important to the people there.

Guided by IBES and School of Public Health faculty member Allan Just and PNPP, Hirsch notes that children are “especially vulnerable to the volatility of weather and so many other health risks of climate change.” As part of her senior thesis, she collaborated with PNPP to produce reports on playgrounds and heat vulnerability children may experience when playing outside at Providence public schools, then asking school leaders if they would consider planting or providing shade to offer students respite from the sun and heat. The partnership allowed her to contribute to and learn from PNPP’s ongoing work “because they are already doing school tree plantings…we were trying to see, how can we use data to to help prioritize those plantings and also understand what are the risks that our children are susceptible to and how can tree plantings be directed in in the most equitable and health forward way.”

The collaboration has been a success, culminating in planned tree plantings at two schools later this spring, funded by PNPP’s newly received $50,000 grant from RIDEM's Tree Equity RI grant program. “The specific site plans for planting will be created in part using the shade mapping analyses that Tabatha and Professor Just have been working on,” Schmolka notes and will help PNPP “meet the demand for schoolyard plantings that we hear from community members all the time.” Yet the benefits are broader and lasting: “the methodology will be documented so that we can replicate it moving forward at other sites across the city,” enabling PNPP “to make strategic choices that maximize the health benefits of tree plantings.”

The reasons for differences in the existing tree canopy are complicated, including zoning and environmental policies and enforcement practices, as well as disinvestment in communities of color. “Spatial analysis is not just about understanding what is happening,” says Şalap-Ayça; “it’s about understanding where it’s happening and how that location shapes the outcome…. For example, tree canopy coverage, heat vulnerability and socio-economic disparities are deeply intertwined and spatial analysis helps uncover how proximity and clustering of these factors impact different communities in Providence. In my GIS courses, I emphasize the importance of using these analytical skills to engage with real-world challenges and to make data more accessible and actionable for communities. Projects like Noreen’s work with Tree Equity Score maps show how spatial analysis and mapping can provide new insights while ensuring that the data aligns with how local residents experience their neighborhoods. By incorporating these perspectives, students are not only sharpening their technical skills but more importantly they are also contributing to more equitable and informed decision-making processes.”